With some new data out from the Canadian Housing Statistics Program (CHSP), it’s time to check some of my past work! Let’s see how it holds up.

First off, I suggested all the way back in January of 2018 that we focus way too much on “foreign” investors as a housing problem in Vancouver. As I noted at the time, I’m not sure why we care if our housing investors are foreign or domestic. But even if we did care, the evidence at the time (compiled from combining data sources) suggested the vast majority of investors were domestic. How does that hold up?

Pretty well! According to CHSP data about four-fifths of real estate investment in Vancouver appears to be domestic, with the remaining fifth is foreign (a.k.a. “non-resident” in Canada*). While I explored this issue by total property value, this matches with Jens von Bergmann’s corresponding estimates by number of owners. I was looking at Metro Vancouver (CMA) as a whole, of course, rather than the City. But the estimates are pretty much the same between the proportion of investors that are non-residents in the City of Vancouver (21.3%) and the CMA (20.9%). The level of foreign investment is high for the parts of Canada studied here, speaking to Vancouver’s transnational connections as a Gateway to Canada. But the differences aren’t that large. Outside Vancouver the range of investment considered non-resident runs from 3.4% in London to 15.7% in the City of Toronto. But returning to my initial point, I’m still not sure why we should care too much which investors are foreign or domestic.

What about investment overall. Are there reasons to privilege owner-occupiers over investors? To the extent investors are offering up their properties for rent we might actually want to encourage investment. After all, renters are generally the most disadvantaged in Canadian housing markets, making up the vast bulk of those in core housing need. So long as investors are renting out their properties, that’s providing more options to renters, which is especially important insofar as Canada’s more or less stopped building purpose-built rental apartments in recent decades and Vancouver has especially low vacancy rates. If investors aren’t renting out their properties, then maybe consider putting in place an empty homes tax! They seem to be gaining in popularity!

But maybe you still want to give people interested in buying a home to live in a leg-up over people interested in buying a home to rent out? This is a common policy choice (see, e.g., principal residence tax exemptions), often justified as building the middle class, helping the young in their aspirations, etc. Theoretically it could also work to challenge landlord monopolies. But in practice, it tends to advantage households in one economic strata (aspiring middle class) over two others (tenants and small-time landlords), while the big-time landlords owning purpose-built rentals may actually benefit from the reduced competition for tenants. Setting aside the various justifications, is there much difference between places in terms of overall investment?

What really jumps out in the CHSP data is the non-metropolitan parts of NS, ON, and BC. Many of the properties in these locations are probably vacation homes. Next comes the City of Vancouver, where 34% of properties appear to be investor owned, followed by London, ON (CMA) at 30%. Yes, just to emphasize the point: the City of Vancouver (highest foreign investment) and London CMA (lowest foreign investment) have remarkably similar rates of investment overall. Huh. (GOTO: why should we care which investors are foreign or domestic?)

But it’s also worth noting that the City of Vancouver is unusual insofar as it’s at the heart of a much broader metropolitan area. We only have data on two other municipalities here: Halifax and Toronto. For Halifax, the City and the Metro Area are exactly the same thing. For Toronto, after amalgamation, the City includes a full 44% of the properties within its broader Metro Area. For Vancouver that figure is only 25%. In short, the City of Vancouver is a very particular slice of its broader Metro Area, while the City of Toronto includes more of its suburbs and Halifax offers the whole enchilada. Looking at broader Metro Areas (CMAs), Vancouver doesn’t stand out much. It’s still on the higher end of CMAs studied, but there’s greater investment overall in nearby Kelowna, not to mention London and Kingston.

Let’s look at another recent blog post, this time exploring condominium apartment use, and co-authored with Jens and UBC’s Douglas Harris. This was a lot of fun! We drew on census data from 2016 and contemporaneous rental vacancy data to estimate empty condos as well as those occupied by renters and owner-occupiers. One of our main findings was that for every ten condominium apartments in a place like Vancouver, we get about six owner-occupied, three rented out, and one left “empty” at any given point in time. Jens turned this into some beautiful “waffle” charts, demonstrating variation across some major metro areas.

Looking only at our estimates of owner-occupation for some of the metro areas covered, we see our estimates from 2016 line up pretty well (within a couple percentage points) with CHSP data for 2018 in the metro areas of Vancouver, Toronto, Hamilton, Victoria and Kelowna. Greater Victoria Ottawa-Gatineau** saw the biggest difference between our estimates from 2016 and CHSP estimates from 2018, with the latter showing higher owner-occupation. This might reflect either historical change or differences in methods, or a combination of the two. All and all I’m counting this as a win!

I also enjoy validation with regard to another one of our key points: investment in condominium apartments is generally much higher than in other forms of housing. Compare the two figures above! Non-owner-occupied condos range from a low of 36% (Peterborough CMA) all the way up to 87% (London CMA). Wow! That’s much higher than the range for properties as a whole, maxing out at 42% in non-metro Nova Scotia. The heavy investment in condominium apartments probably has to do with the financing model, which is heavily dependent upon pre-sales. Usually people buying a place to live need it immediately. But investors can afford to wait and thereby take a stronger role in providing the capital to help develop new housing. Overall, this accords with the effective replacement of purpose-built rental apartments (held by big landlords) with condominium apartments as rental stock (distributed among small landlords). There may still be very good reasons to favor purpose-built rental apartments (security of tenure being a big one), but until financial models and incentives for them catch up to the attractiveness of condo developments, we’re kind of stuck with the latter as a big source of market rentals.

The shift to condominiums as rental stock also demonstrates an important compositional issue. Places with lots of condominiums can have much higher rates of investment overall, even if their condominium stock is more often lived in by owner-occupiers. Where do we see the most condominium stock? Hello Vancouver!

In terms of use of condominium apartments, both metropolitan Vancouver and Toronto are both at the low end for investor ownership, just a percentage point ahead of Peterborough (37%). The City of Vancouver is a little closer to the middle (46%), but still on the low side. But condominium apartments dominate the overall stock of properties in Vancouver, driving up the overall investment we observe. Just to round things out, let’s drop condominium apartments from the mix, and look at other residential properties that could potentially be occupied. Dropping condominium apartments (where Vancouver is on the low side of investor ownership), we see that the Vancouver CMA is decidedly in the middle of the pack on other kinds of property investment. The City of Vancouver still runs a little bit high (up there with the Kingston CMA), but nowhere near the non-metropolitan areas. The dominance of condominium apartments explains away a lot of the investment patterns we see in Vancouver.

Overall I’m feeling pretty good about my past work! (And even better about the work of my collaborators – they’re sharp!) But I’m not quite as excited about the way the CHSP data has been reported on in the media. Given a barrage of stories about foreign investors and “toxic demand” driving broader Vancouver housing crises, it might be time to look at the data in comparison and see that we don’t really stand out in most ways.

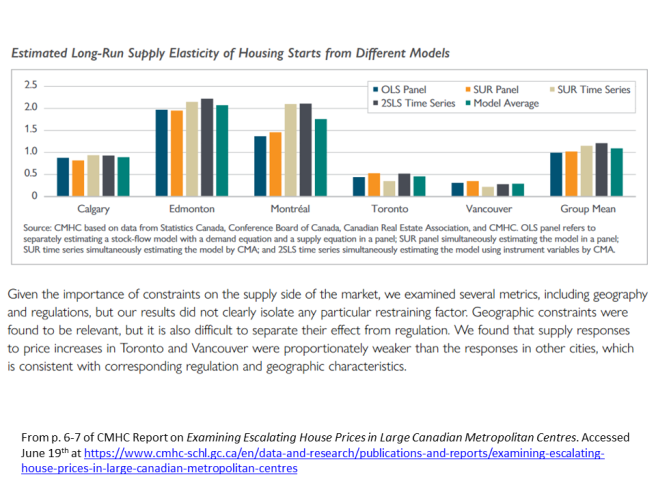

Where do we really stand out? Well, as the CMHC notes it’s not about toxic demand so much as toxic supply elasticity.

Translating that finding: we’re a city and region where a lot of people want to live that hasn’t built enough housing, market and non-market alike, to maintain affordability and keep everyone who wants to live here well-housed. Guess there’s only so many times that’s going to make for good headlines.

Want to play around with the data yourself, but not ready for R? Go to the Statistics Canada’s portal to run your own cross-tabs, or see my handy excel spreadsheet here.

*- “Resident” vs. “Non-resident” status refers to where owners are located in CHSP data, rather than to their citizenship. Owners located abroad are considered non-resident, even if they’re Canadian citizens. I only look at “applicable” properties eligible to be occupied by their owners in this analysis, ignoring the minority of properties where occupancy is considered “not applicable.” For a look at corporate ownership structures, have a look over at Jens’ recent post!

**- Oops! Initially somehow mixed up Ottawa-Gatineau with Greater Victoria. Looking more carefully at the geography here, it appears that CHSP only tracked data on the part of Ottawa-Gatineau inside of Ontario, which may also account for the larger variation from our 2016 findings, where we included the Quebec part of the CMA as well.