(co-authored with Jens von Bergmann and cross-posted at MountainMath)

A spectre haunts housing policy. The spectre of empty homes. So how many empty homes are out there?

Unfortunately, inept analyses of census data often leaves us with incomplete, or even worse, completely wrong answers to this question. When we get data on empty homes for a given city, they’re seldom put into comparative perspective. What’s worse, sometimes when they’re put into comparative perspective, they’re compared with the wrong data and picked up by credulous media, spreading misinformation. So let’s try to do it right!

Here we want to compare some big metro areas and cities in Canada with similar metro areas and cities in the US. As a bonus, this comparison sheds some light on our incomplete data in Canada, and why empty homes have managed to become so central to Canadian housing discussions.

Empty homes

In Canada we only have one national measure of empty homes, the Census. It estimates the number of dwelling units that are not occupied on census day. It does not offer any insight to why those homes are not occupied. Nor is it part of the standard release data, for most censuses it is only available as a custom tabulation. However, the related number of homes not occupied by usual residents is part of the general census release data and available down to the census block level. It is given by the number of dwellings minus the number of households (aka “occupied dwelling units”), so it includes dwellings that are occupied by people who usually reside in a different “household.” To understand what that means we need to remind ourselves that the census counts people, and tries to count them only once. And each person belongs to exactly one household. This gets tricky for people that call several places their “home”, for example a student that rents an apartment near university but also lives with their parents during summer, or someone working in Fort McMurray for months at a time but lives with their family elsewhere during work breaks. These people may think of their family’s home as “home”, and the other place as “temporary”. In the census, the “temporary” home will be counted as “occupied by temporary residents” and not count as a “household,” as their main household is elsewhere.

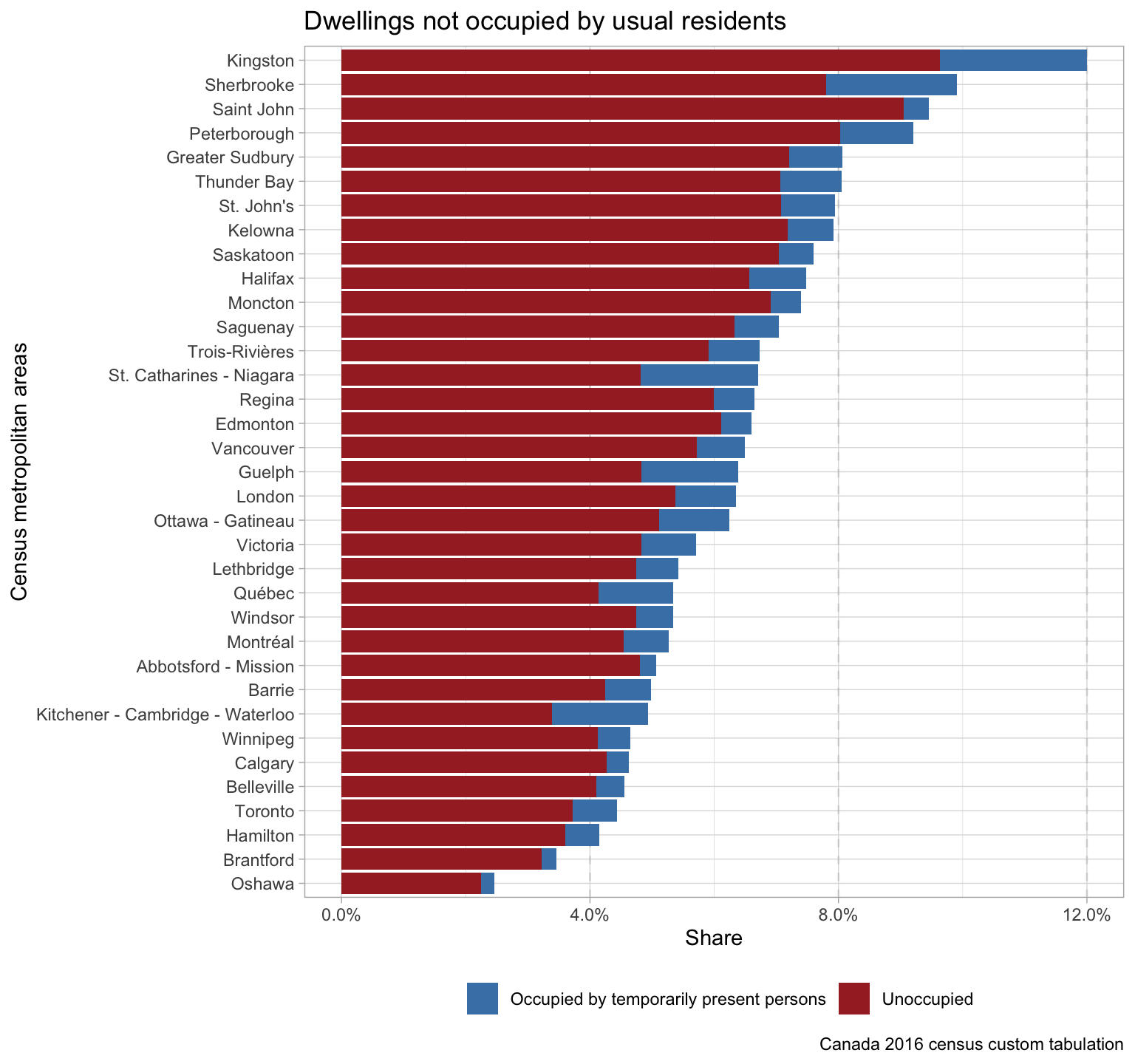

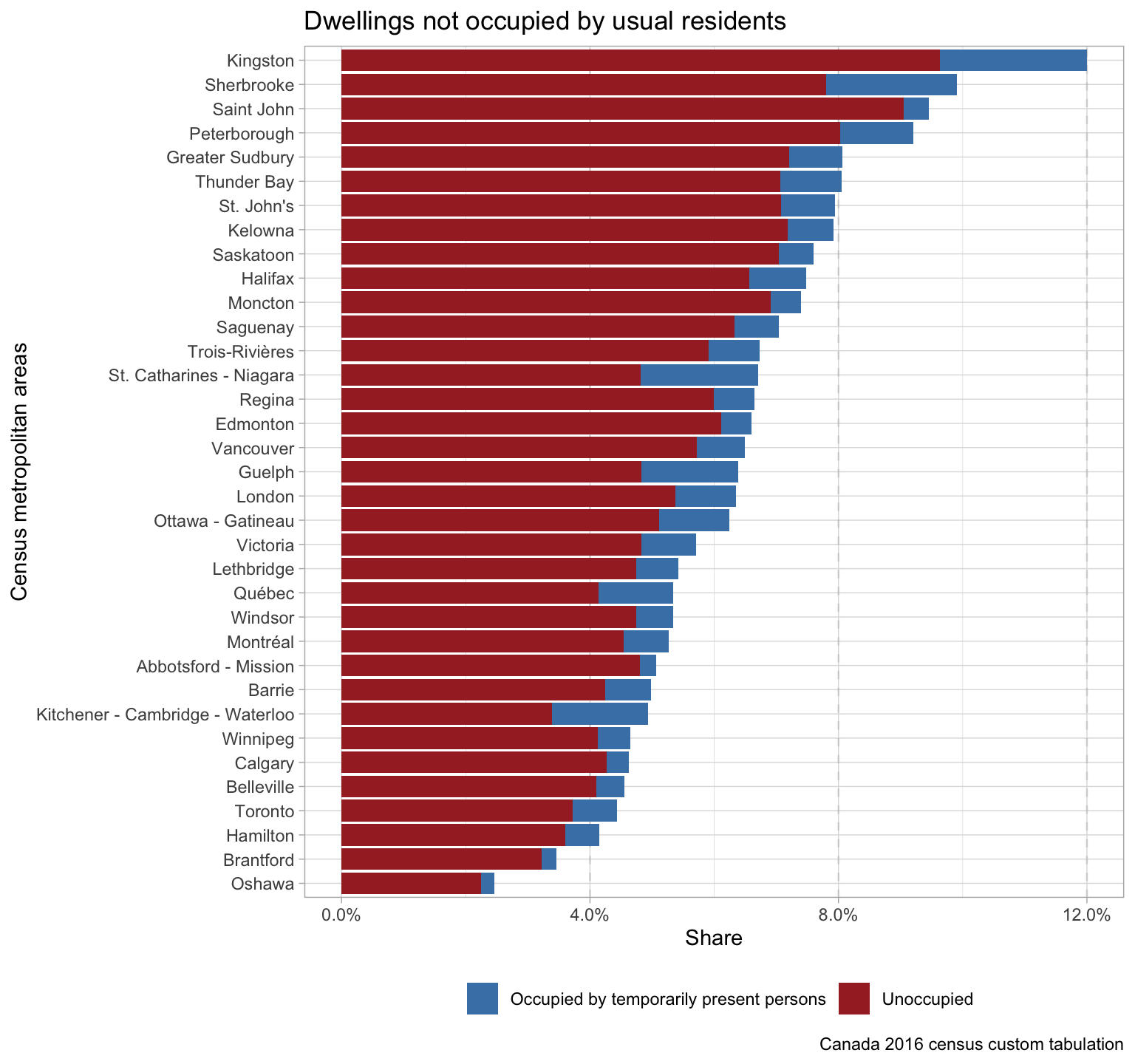

Canadian numbers

Canadian data is pretty simple. To start off we look at Canada’s major census metropolitan areas by their share of unoccupied dwellings. For context we also show the temporarily occupied units. We get a range of unoccupied households somewhere between roughly 2% and 10%, with most bigger metros hanging toward the middle, between 4% and 8% (or what the Lincoln Land Institute considers the desirable range of “reasonable vacancy”).

We can also look at municipalities, keeping in mind that the comparison across municipalities is inherently difficult as different municipalities play different roles within (or outside of) metropolitan areas. Here’s a selection of municipalities, including the boundaries for the old (pre-amalgamation) City of Toronto, just for kicks. Note that municipalities still tend to hang between the 4% to 8% reasonable vacancy range, but the high share of temporarily occupied homes in Waterloo stands out, likely a function of students making up a large share of the town’s population.

US Data

US data on unoccupied homes is available from multiple places. Here we use the American Community Survey as similar to the Canadian Census. (But see also the American Housing Survey for fun cross-referencing).

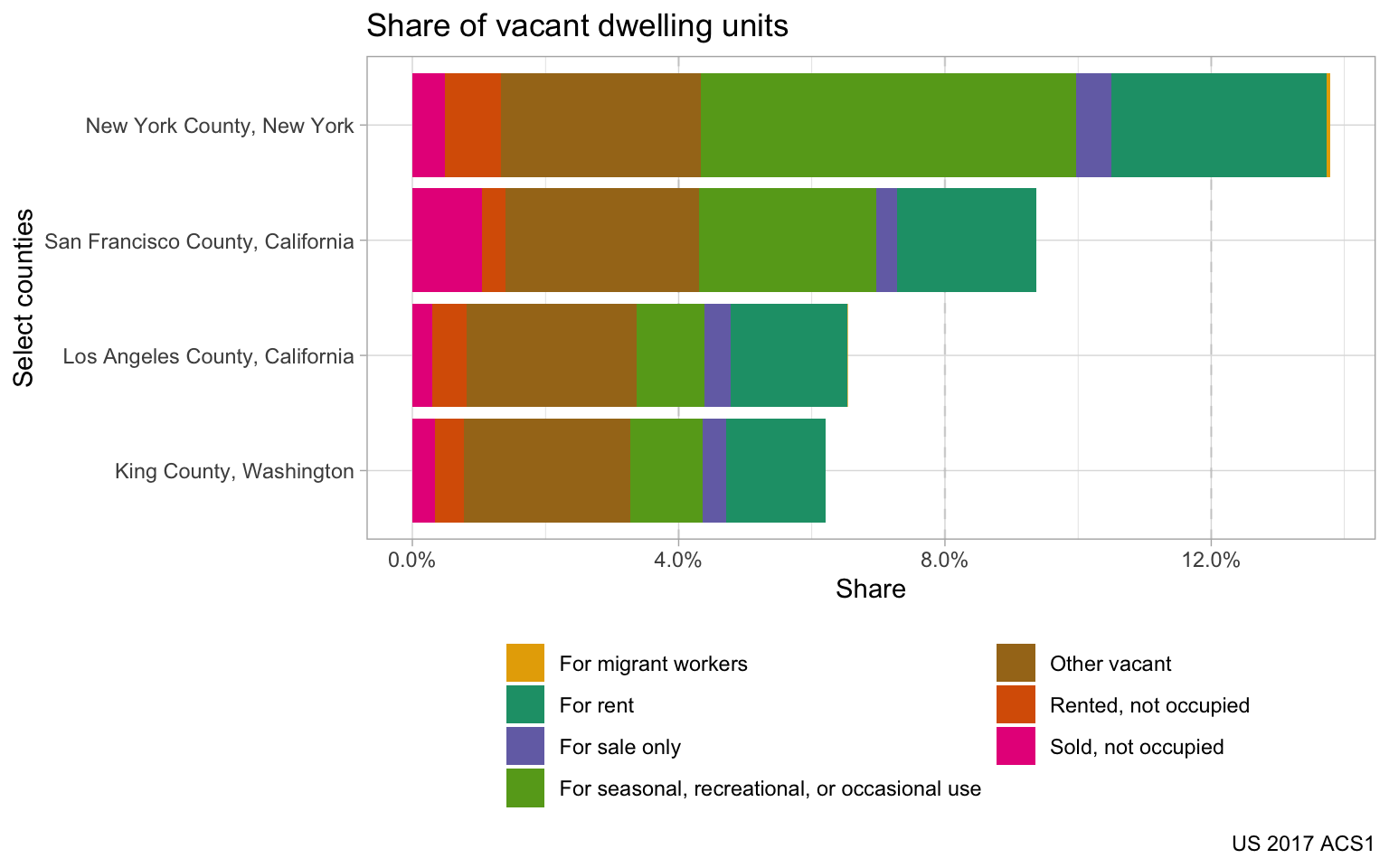

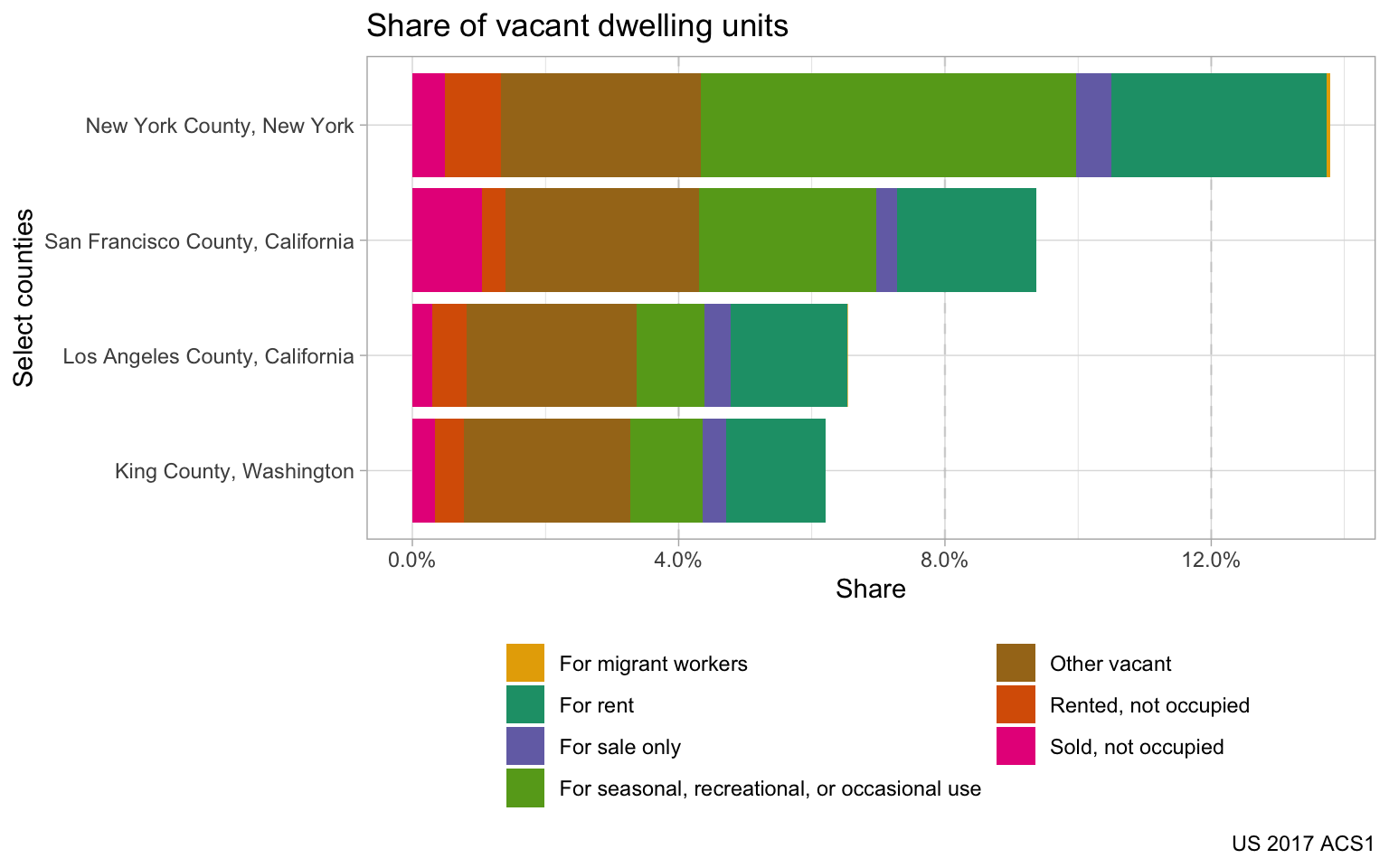

US data is great in that it adds important context to unoccupied units, specifying the reason the unit is unoccupied. This context is often completely absent from Canadian housing discussions. It clearly splits out the transactional vacancies, (units for rent or for sale), from moving vacancies (units sold or rented, but not yet occupied), from recreational vacancies (units for recreational, seasonal or occasional use), from other vacancies (not otherwise accounted for).

The range for US Metropoles is also much higher than for Canada, running 12% and higher in the seasonal vacation-oriented metros of Florida, Arizona, and Southern California. Just below these metros sit some of the rust belt metros (Pittsburgh, Detroit, St. Louis) that have lost population, resulting in higher “other vacancies” from homes left behind. Houston seems driven by a high proportion of dwellings available for rent. Overall the data show that many empty homes may be accounted for by these kind of transactional vacancies and moving vacancies, together comprising vacancies we might also think of as good vacancies insofar as they enable people to move between homes to find the best fit. Down toward at the bottom we see just under 5% in the Twin Cities of Minnesota.

Overall, vacancies tend to be higher in the US than in Canada. As unoccupied dwellings rise much above 5%, they seem to be increasingly explained by recreational vacancies and other vacancies. A baseline of other vacancies remains largely unavoidable (e.g. homes under major renovations, tied up in court cases, etc.), and also appears to include people showing up as temporary residents in Canada. We can use ACS data on Usual Residence Elsewhere to provide figures similar to what we get in Canada, comparing all North American metros on roughly the same basis. Here we’ll just show the 14 biggest US metros along with the 6 biggest in Canada.

Overall Canadian metros tend to have lower vacancy rates (combining unoccupied with temporarily occupied) than US metros. Seasonal destinations (Miami and Phoenix) – that also provide second homes for many Canadians – top the vacancy rates for large metro areas, followed by a diverse mix of large metros. Edmonton and Vancouver, though high for Canada, fit very comfortably in the low end for the US (running from Seattle to Boston), while Toronto, Calgary and Montreal occupy the bottom.

What of the bad kind of vacancies, often associated with second or higher order homes for the wealthy or holding properties off the market for speculative purposes? Empty Homes Taxes and Vacancy Taxes in Vancouver and BC attempt to target just these kinds of dwellings, and so far they indicate that just over 1 in 9 unoccupied units end up getting taxed as second homes or otherwise vacant without defensible cause. Vacancy data from the US suggests that were such taxes imposed in places like Miami, that figure would likely be a lot higher. But Miami markets itself as a seasonal or vacation destination.

Vancouver’s Empty Homes Tax covers the City. BC’s speculation tax covers a region larger than cities or even any given metropolitan area. Just for kicks, let’s peek in on counties, a unit of governance in the US with no firm equivalent in Canada. Weirdly, counties can contain portions of cities, like New York County, which contains only the island of Manhattan within NYC. Sometimes counties are the same as cities, as seems to be the case for San Francisco county. Other times counties are a little larger, as with King County (containing Seattle). Sometimes they’re much larger, as with LA County. How heavily would vacancy taxes likely fall in these various counties? In the counties acting like metropolitan areas, including King County and LA County, overall unoccupancy rates are similar to Metro Vancouver. Vacation homes would likely be hit unless deemed ineligible for year round use. Some, but not all, other vacancies would likely be taxed. The vast majority of empty units probably wouldn’t remain empty long enough to trigger taxation. Counties containing Manhattan and San Francisco, with much higher seasonal use, would probably be hit much harder.

Altogether, unoccupied dwellings are broadly similar between the US and Canada, with slightly more dwellings showing up as unoccupied in most metro areas to the south. Lots of municipalities, regions, and counties might profitably consider Empty Homes or Vacancy Taxes. But most unoccupied dwellings in most metros wouldn’t be much affected by them.

Code linked at GitHub!