Public intellectuals beware! Not everyone agrees with you, and some will be nasty about it. So how does it work when muck-raking journalists attack?

First some context: an observation of mine on twitter led to a little dust-up concerning the discourse around “foreign money” in Vancouver. I quickly muted the conversation, but it summoned many trolls, including the ghost of Margaret Wente (which paradoxically made me feel all warm & fuzzy, like I’d done something right). South China Morning Post reporter Ian Young, one of the chief troll-masters, decided to put out the equivalent of a journalistic hit on me. I suspect this is a pattern with Ian, given his past attacks on other public figures he disagrees with (like UBC’s Tsur Somerville). So I’m posting my responses here for future reference. Hopefully this will serve three purposes: 1) it may help keep Ian honest in his muck-raking; 2) it may have broader lessons for other academics who dare raise their voices in the rough and tumble public sphere; and 3) some people might actually be interested in my answers to Ian’s questions.

How things unfolded: After an initial relatively professional inquiry about getting my input on general issues (foreign money, racism, real estate), Ian sent me the following questions, which focus less on my input and more on my conduct, including both my tweet (which brought all the trolls to the yard) and my participation as an expert witness in a court case challenging BC’s foreign-buyer tax. But it doesn’t stop there. Read on if you’re also interested in strata wind-ups, because there’s a part two to the journalistic hit-story where Ian dives even deeper to try and find dirt on me!

Ian’s initial questions [in bold]:

- In your affidavit in the Jing Li case, you say the role of “foreign buyers” in the Vancouver real estate market has likely been exaggerated. How big a role do you think “foreign money” – specifically, Chinese money (brought by both immigrants and non-immigrants) – plays in the Vancouver real estate market?

“Foreign money” is a problematic and sloppy concept, especially as applied to the wealth immigrants bring with them. I think immigrants play a strong role in driving Vancouver real estate, and we attract a disproportionate share of wealthy immigrants. We can talk immigration policy, and while I’m generally pro-immigrant (and an immigrant myself), I’m on the record against “investor” immigration programs. But when people immigrate to Canada, I no longer think of their wealth as “foreign.”

It would appear from data I’ve seen and analyzed, as compiled by the CMHC and Statistics Canada, that the role of people investing in Vancouver real estate while living elsewhere is a real but relatively small part of the local market. The evidence suggests local investors are far more prominent.

As for the issues of tax avoidance and money laundering (that people sometimes pretend only apply to “foreign money”), I take it for granted that these are bad things that should be ended regardless of how big a role they play in real estate.

- Can you elaborate on the role of racism in the debate over foreign money and Chinese money in the Vancouver affordability debate?

I believe a number of different logics or motivations have driven the debate over “foreign money,” which as I’ve mentioned, I consider a problematic and sloppy concept. Many people are drawn to the “foreign money” explanation as a ready answer to their understandable confusion over prices that keep them from obtaining housing they feel like their parents might’ve been able to afford or that they could still easily obtain in other parts of Canada. They’re looking for answers – especially answers that don’t make them feel like failures for not achieving their particular homeownership goals, which are often associated with middle-class success, becoming an adult, and being a good parent. In this sense, there’s a real moral and personal element to debates over housing. And people are right to look beyond their own circumstances for explanations into Vancouver’s affordability woes. It’s a very sociological instinct!

But blaming foreigners isn’t helpful and the distinction between foreigners and foreign money isn’t very clearly drawn, just as blaming Chinese people isn’t helpful and the distinction between Chinese people and Chinese money is fuzzy at best. Racism certainly plays a part in the popularity of “foreign money” discourse, and Vancouver has a long and troubled history there. But we’re also in a very broad-ranging and very real populist moment where a generalizable xenophobia has taken root around the world. It takes different forms in different places, but it troubles me wherever I see it. Then there are also dynamics that are quite specific to Vancouver and its waves of immigrants from Hong Kong and Mainland China (and to a lesser extent, from Taiwan). Many people from Hong Kong are understandably worried over the future of their home city, seeing both Hong Kong and now Vancouver as threatened by Mainland China. These worries are frequently expressed through anti-Mainlander prejudice. I don’t think the term “racism” captures all of these logics or motivations, but it’s part of a somewhat toxic brew that in Vancouver is often targeted at Mainland China and Mainland Chinese.

- Can you explain the continuum of racism in BC and what role it plays in government policies and public opinion relating to real estate here?

As you suggest in your questions, the debate about “foreign money” and “foreign buyers” was also particularized by many people as a debate about “Chinese money” and “Chinese buyers.” People moved back and forth between identifying Canadian sovereignty (vs. foreign) as their primary concern and targeting a particular nationality (“Chinese”) as a concern. My understanding is that anti-Chinese sentiment takes many forms, including those driven by race-logics and racism (and particularly prominent in Vancouver’s past), and those driven by logics and motivations internal to the Chinese diaspora that aren’t racial in nature, but rather reflect tensions with the Mainland. Anti-Chinese sentiment has historically played a very strong role in government policies in Vancouver and BC more broadly. Both governments have acknowledged and apologized for this, but I believe it would be naïve to suggest anti-Chinese sentiment no longer plays a role in driving policy.

- Regarding your “national socialism” tweet…were you offering a sincere observation, or being deliberately hyperbolic?

It was a sincere observation, but couched as a worry rather than an accusation. Indeed, I went out of my way to grant good motivations to those involved in the discussion. My worry involved an underlying transformation in logic. Socialist logics focus on privatized wealth & related inequality as a problem. National socialist logics veer far to the right by twisting concerns about inequality to focus on particular groups of people, demonizing them as enemies of the nation and identifying their wealth or perceived power alone as the problem. To return to our local discussion, it isn’t hard to find far-right, pro-fascist organizations cheering on discourse about “Chinese buyers” and “Chinese money” being to blame for Vancouver housing woes. To put this in very simple and personal terms: if you think “foreign money” is the problem and you focus on the money part, I’ll be with you. If you think “foreign money” is the problem and focus on the foreign part, I won’t. This relates to what I think of as quite important underlying shifts in logic that are very pertinent to the present moment in time.

- Where do you want the policy debate over real estate affordability in Vancouver to go? What areas deserve more emphasis than addressing foreign money and foreign buyers in the market, as a means of improving affordability, and why?

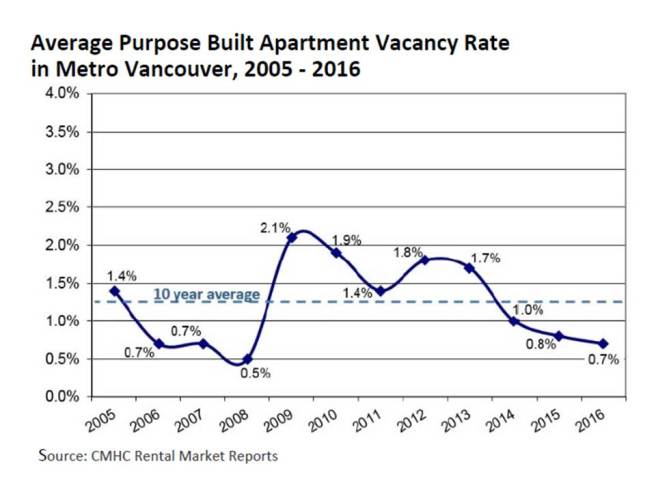

The most important aspects of affordability in Vancouver often get the least amount of attention. Those people currently marginalized by the market distribution of housing, including the homeless and those living in core housing need, should receive the most attention. They are the ones for whom housing is a life and death matter. Temporary Modular Housing is a great move here, and that and related programs should be expanded. Next we should focus on renters. They’re the ones in dire need of more options (Vancouver’s vacancy rate being at 1%) and at most risk of falling into core housing need. There are lots of policy options here, and we should be creating way more social housing options, including a big expansion of non-equity cooperatives. We should also encourage and enable many more market options. Far behind these groups, we get to owners and those desiring to own. There are real benefits to having a very large and broad range of property owners rather than letting property ownership accrue only within a very small and select class. There are also real benefits to having lots of different kinds of housing stock that enable a broad range of options for people to pool their resources together and buy housing, while also encouraging more environmentally friendly lifestyles. I don’t think we need any more programs encouraging and promoting home ownership, which is too often where affordability debates take us, but I don’t think it should be discouraged either.

- What were the circumstances that led you to provide your affadavit in the Jing Li case?

I was approached by the law firm representing Jing Li to act as an expert witness in the case. Representatives of the firm very clearly and repeatedly assured me that as an expert witness, my duty would be to the Court rather than the law firm or their client. This was an important part of my decision to accept the role of expert witness. Through my work as an expert witness, I carried out research to answer questions posed to me by the law firm (through my letter of engagement), with my obligation being to provide truthful and well-researched (“expert”) answers to the Court.

The story continues

These were Ian’s first questions, and I initially agreed to delay blogging my answers until around the time Ian’s article came out. But after his first round of questions, Ian sent me follow-up questions focused solely on my conduct and concerning my former strata association’s wind-up and sale. He’d tracked down the buyers of the strata and apparently identified them as the very personification of evil “Chinese money.” So he sent me targeted questions about this being an unidentified conflict of interest influencing all of my public commentary. “It turns out that disagreeable professor was being paid by ‘Chinese money’ all along! Now we’ve got him!”

It’s a bit of a scoop! But not in the way Ian thinks. As I’ll discuss below, the strata wind-up was a complicated process that I felt ambivalent about, and I knew very little about the ultimate buyer. I’ve been planning on blogging about the experience of being part of a strata wind-up from the inside, but I’ve delayed for a variety of practical reasons. Now my story is in danger of being scooped by someone else! So let me tell you a little bit about what went down before Ian does whatever he’s going to do with his take.

What about my strata wind-up and sale?

My partner and I were initially quite angry when news broke that our strata council was considering looking at winding up the strata and putting it on the market. We liked our townhouse just fine, and we hadn’t been there very long. Ours was a mixed strata, comprised of townhouses and a low-rise building. The main issue seemed to be that the low-rise building was worried about their expenses, which were treated separate from ours, and wanted to compare estimates for fixing the place with what they could get for selling the place. We initially took this to suggest that the low-rise hadn’t been keeping up their building the way they should, and it didn’t seem fair that we in the townhouses should have to sell to cover their expenses. But then the possibility for big money from a sale also started getting thrown around in a lot of conversations with neighbours. Some were very excited by the prospect. Others were noticeably distraught that they might have to leave. After much discussion and many meetings, the strata as a whole voted to market the place to see how much it could sell for. Working with Colliers, we ended up with an offer that entailed a lot of money (around twice our assessed values). We knew very little about who made the offer, but the realtors told us it was a new developer with interests both in Canada and China. Then we had a vote on whether or not to accept the offer and wind-up the strata. My partner and I were conflicted in our voting. A lot of money was on the table, but we really liked our place and sympathized with those who wanted to stay. In the end our vote didn’t matter. The vote to sell easily met the threshold required under the new strata wind-up regulations.

There were minor complications throughout – it’s a big and involved process to wind-up and sell a strata – and we still weren’t certain the deal would go through for several months after the vote. In fact, we kind of hoped the deal would fall apart (especially when the flowers came out in our little townhouse yard!) But eventually all the t’s got crossed and the i’s dotted. And now we’re renters! (We negotiated a period of time in which we could rent back our properties while looking for someplace new to live).

Overall, the strata wind-up and sale is something that happened to us, rather than something that we actively sought. We weren’t at all certain we wanted it to go through. I learned lots from it, but it did not otherwise affect my public commentary* and I did not know who the beneficial buyers were until Ian sent me their names, nor have I ever had contact with the beneficial buyers. As in most real estate transactions, their identities were never anything more than a curiosity throughout the process. I remain curious, as ever, about what they’ll do with the place once we’ve all left. Until then, speaking as a tenant, if Ian wants to dig up dirt on my new landlords, I’ve got no problem with that.

*- There is one exception regarding the strata wind-up and sale affecting my public commentary! My partner and I are dual-citizens, and as a result we’ll be paying capital gains taxes on the sale to the USA, where sales of principal residence are not exempt from taxation. We don’t mind this in principal, and we kind of feel like windfall gains should be taxed. But we really, really wish our taxes were going to Canada. So its possible my advocacy for taxing the profit on sales of principal residences in Canada has been strengthened by the strata wind-up. Take my money Canada! Please!