Co-authored by Jens von Bergmann and cross-posted at MountainMath

Many Canadian municipalities are implementing reforms to allow multiplexes in formerly single family areas. These initiatives are driven by provincial reforms and federal incentives to increase housing supply. We review the findings from our recent paper studying the outcomes of multiplex reforms in Kelowna and Coquitlam that emphasize that implementation details matter, and take a look at early indicators of how multiplexes are faring in Vancouver since the City passed its own multiplex bylaw in late 2023.

From books to blog posts, we’ve long been on the record advocating for reforms to the regulation of low-density urban lots, enabling more people to share less land (e.g. (Lauster 2016; Dahmen, von Bergmann, and Das 2018; von Bergmann and Lauster 2021, 2025)). On all of the lots zoned to protect single-family detached housing – North America’s “Great House Reserve” – the most obvious reform has been to enable multiple families to divide up space instead. Reforms changing low-density zoning to enable duplex, triplex, and increasingly multiplex running to 4-6 units per lot or beyond, all seem like easy solutions to housing shortages. Vancouver was an early leader in many of these reforms via enabling secondary suite and laneway houses, but recently it seems like it is falling behind, even after a much touted shift to the R1-1 zone putatively allowing multiplexes across most of the urban landscape. As it turns out, housing regulation has grown quite complicated, and restrictions on the number of dwellings per lot aren’t the only things holding back additional housing on low-density lots. When it comes to enabling multiplexes, the devil is in the details. In this post, we first step outside of Vancouver to highlight some of our recent research into the details of multiplex reforms elsewhere in BC, and then return to the City to see how multiplex are faring locally.

Working together with colleagues, we explored the current progress and future potential of various multiplex reforms across BC on behalf of the province. We noted that two communities, Kelowna and Coquitlam, upzoned about 800 single family parcels to allow four-plexes, Kelowna in 2016 and Coquitlam in 2019. We investigated the outcomes of this upzoning for our 2023 modelling report for the provincial Small Scale Multi-Unit Housing (SSMUH) legislation. (von Bergmann et al. 2023) While these two upzonings looked quite similar on paper, they had quite different outcomes. This observation underlines the difficulty in modelling outcomes of the provincial legislation insofar as they left implementation details up to municipalities. We added very strong caveats throughout the analysis that our report assumed faithful implementation not just of the broad parameters of the legislation but also the full intent.

Subsequently, we felt that it would be worthwhile to turn the sections on Kelowna and Coquitlam into a more formal study to further quantify the effects of the two upzonings and turn this into a paper, which just came out. (von Bergmann et al. 2025) This more formally quantifies the ways in which these two reforms that look very similar on paper differ in real word outcomes.

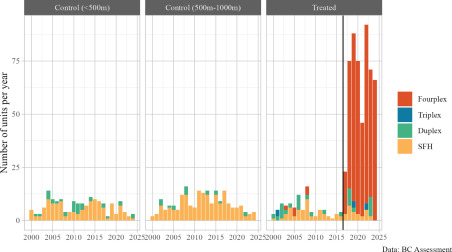

At a high level the impact of the multiplex zoning changes in these cities can be seen in Figure 1, which shows the annual number of SFH, Duplex, Triplex and Fourplex dwelling units completed in the upzoned area as well as several “control” areas for each of the two cities.

Figure 1. Comparisons of multiplex reform outcomes in Kelowna and Coquitlam

(b) Coquitlam

The reasons for the difference in outcomes are complex, and we don’t have a full understanding. The biggest difference that we suspect matters here is that Kelowna focused on fast permit times, setting up pre-approved (outright) designs with very short permit times, and relatively fast permit times for general applications with different designs. One detail here is that the design competition for the fast-tracked pre-approved designs required architects to work in conjunction with developers to ensure that there was interest to actually build these. By contrast with Kelowna’s fast-tracking, permit times in Coquitlam were significantly longer, involving detailed conditional review and introducing significant risk into the development process that small builders are often ill equipped to handle.

Another difference was parking requirements, with Coquitlam requiring two parking spaces per unit while Kelowna only required one. Minimum lot width in both Kelowna and Coquitlam guaranteed that there was enough space for four parking spaces, and Coquitlam allowed the two parking spaces for each unit to be stacked, so the outer car would have to get moved in order for the inner car to get in or out. This seems like a drag, but we don’t believe parking requirements strongly constrained the number of lots where four-plexes could physically be built. Rather the Coquitlam requirements may have significantly constrained the design of four-plexes and degraded the usable outdoor space. Could be an issue, but probably not as big a deal as the permitting process.

The biggest takeaway of our comparative research is that the details of multiplex reforms matter, particularly as they apply to simplifying the process for developers, reducing timelines and providing certainty to outcomes. So let’s return to the City of Vancouver’s reform!

Vancouver multiplexes

The province drew upon our research in formulating its Small Scale Multi Unit Housing (SSMUH) reforms, mandating all municipalities allow multiplex on previously single-family lots (as of November 2023). The City of Vancouver was working on its own multiplex reform, and snuck under the wire by passing a bylaw that reclassified single-family lots to multiplex in October of 2023, just before the lots at issue would have come under provincial regulation.1 We take this as an occasion to take stock of how Vancouver multiplexes have fared so far. We don’t have enough data to do a thorough analysis like we did for Kelowna and Coquitlam, but there is enough to take a preliminary look.

Prior to the multiplex legislation Vancouver allowed three units on most single family lots at 0.85 FSR under single ownership or up to four units structured as two strata lots with a main unit and a lock-off suite each for a combined 0.7 FSR. The multiplex legislation allowed for more freedom on how to configure units and increased the allowable density to 1 FSR. However, going beyond duplex and additions to floor space both remained conditional uses rather than outright, requiring contributions of various sorts to the City and close planner review. Contributions to the City were subjected to value capture analysis intended to balance out construction of multiplex with single detached and duplex. Subsequently the bylaw has been amended to allow up to six units in frequent transit areas as well as an expansion of the area that allows for multiplex as required by provincial SSMUH legislation. Of note, the density requirements remain far below the provincial guidelines of an implicit 1.5 to 1.6 FSR despite being in one of the the highest demand areas in the province.

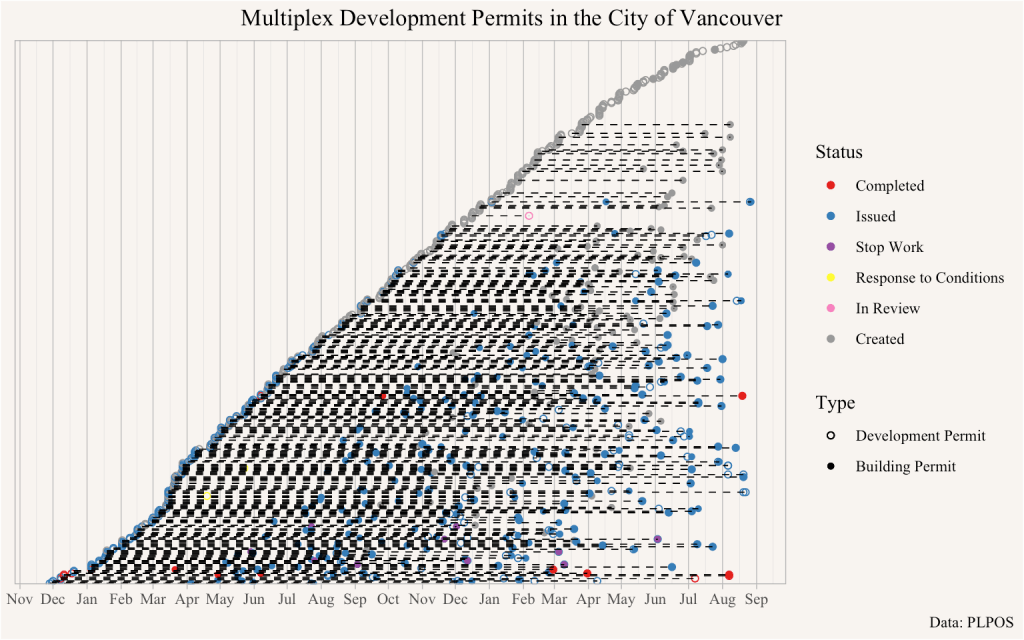

So far in Vancouver there have been 429 development permit applications for multiplexes, of which 143 have been issued (or completed) and subsequently 123 building permits have been issued (or completed).2 Table 1 table gives a more detailed breakdown.

Table 1. Vancouver Multiplex Applications by Permit Status

| Type | Status | Number of multiplexes |

|---|---|---|

| Development Permit | In Review | 45 |

| Development Permit | Preparing Recommendation | 2 |

| Development Permit | Response to Conditions | 168 |

| Development Permit | Approved Subject to Conditions | 71 |

| Development Permit | Issued | 137 |

| Development Permit | Completed | 6 |

| Building Permit | In Review | 114 |

| Building Permit | Stop Work | 5 |

| Building Permit | Ready For Issue | 1 |

| Building Permit | Issued | 119 |

| Building Permit | Completed | 4 |

Our data does not come with clean unit counts, a scan of permit detail descriptions indicates that a little below half of multiplex applications are for fourplexes, with the next popular configuration being triplexes at around 30%.

Figure 2 shows how multiplex applications have been progressing.

Starting the clock in November of 2023, development permit applications are coming in at an average pace of 23 per month so far, or about 273 per year, almost double of the 150 applications a year that Vancouver staff originally projected. Translated into a redevelopment rate of the roughly 69,000 eligible single family parcels in Vancouver this means that at the current rate each parcel has about a 0.4% percent chance of redevelopment each year, about double what Coquitlam saw after their upzoning but less than a tenth Kelowna’s outcomes.

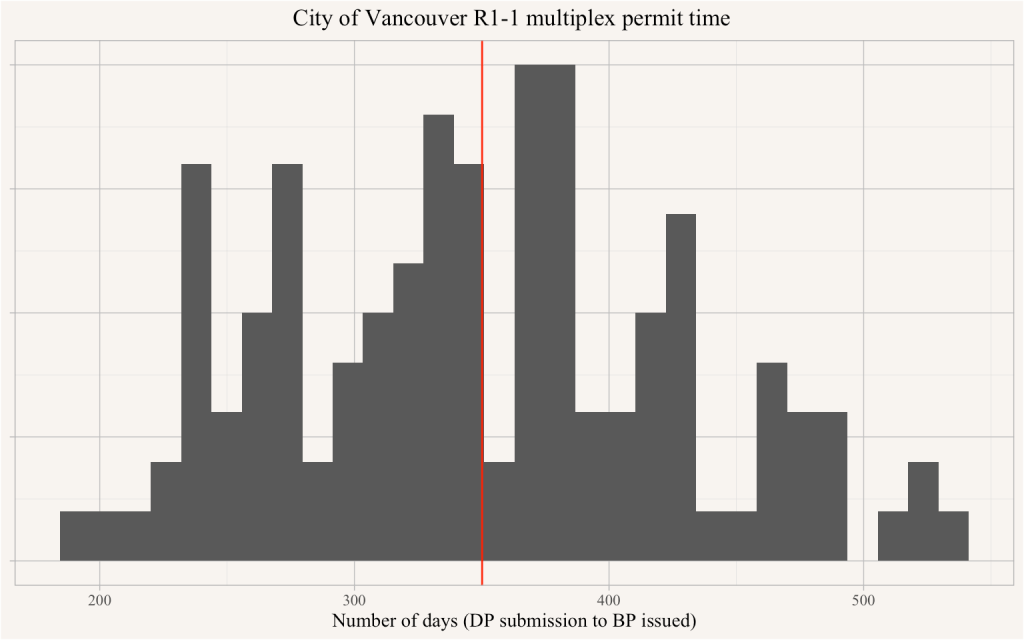

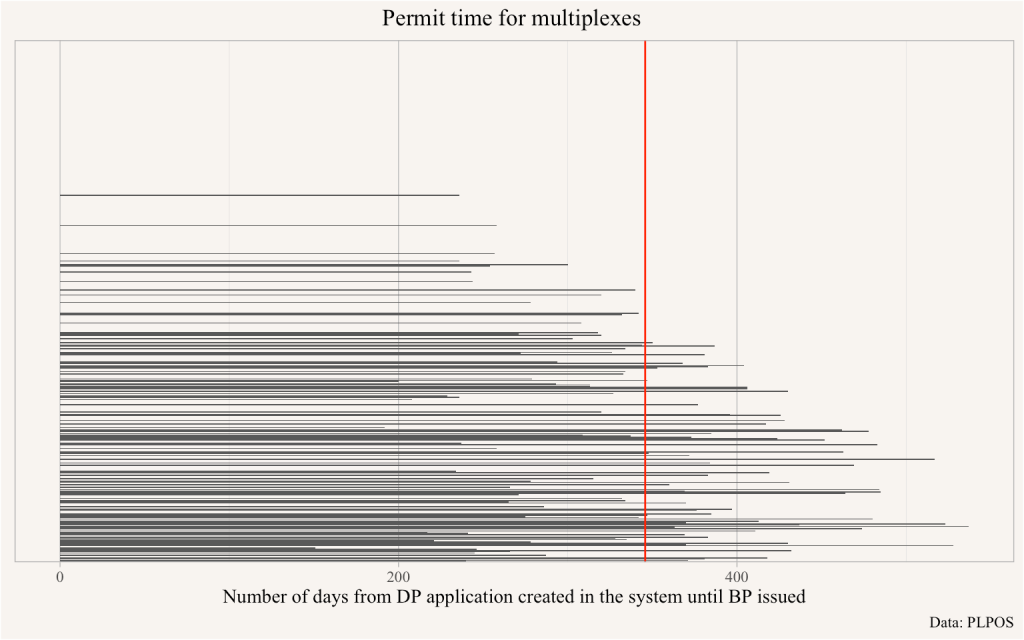

Figure 3 shows the distribution of permitting timelines, from creating of the development permit to issuance of building permit, conditioning on having an issued building permit. The right-censored nature of the data makes it difficult to give definitive statements about permit times, a strong lower bound on permit times derived from is 350 days, with a wide distribution ranging from very fast permit times of 200 days at the low end and over 500 days at the high end so far.

Figure 4 shows permit timelines ordered by creation data, with blank lines where building permits have not yet been issued.

A naive interpretation might suggest that permit times are decreasing, but it would be foolish to conclude that from this graph. The blank spaces of projects that have not yet received a building permit highlight the right-censored nature of the data and signal projects with outstanding permits that, once they get issues, will necessarily have longer permit times than nearby (in terms of creation date) permit applications that have already been issued building permits. Vancouver council’s 3-3-3-1 Permit Approval Framework, which suggests that multiplex permits should be given in 3 weeks, is clearly not working yet, and there is no strong indication of improvement in multiplex permitting timelines.

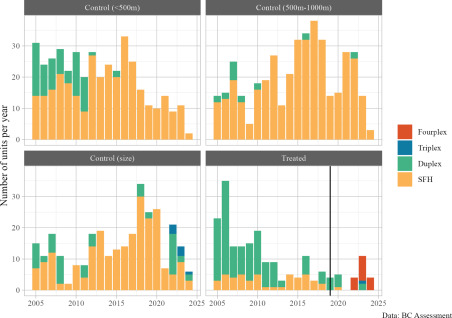

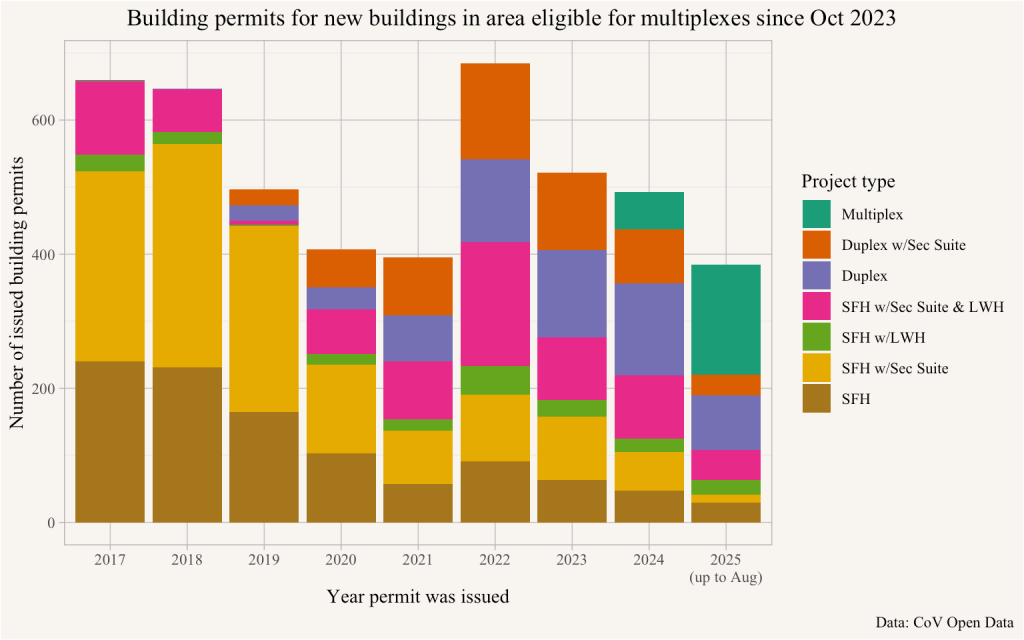

Figure 5 offers a view into the landscape of low-density development in the R1-1, RT-7, RT-9, and FSD zones that legalized multiplexes by tracking issued building permits for single family, duplex, and multiplexes by year the permit was issued.

We see the shift away from almost exclusive single family housing (though often suited and some with laneway houses3) towards more duplexes and multiplexes, but the overall number of low-density building permits has not increased substantially. The multiplex reform has – by design – not led to a significant increase in the overall rate of redevelopment of low-density lots.

So far results from Vancouver’s multiplex reform appear to fall somewhere between Kelowna’s and Coquitlam’s. To be sure, new multiplex have entered the pipeline, but their progress has been stalled by permitting review. Developers continue to fall back on dwelling types (single-family house and duplex) offering less relief for housing shortages but enabled by outright approval processes, as well as those including secondary suites requiring conditional approval processes, but where developers have more experience and certainty working through permitting processes.

It’s worth noting that Vancouver’s overall density of 1 FSR is higher than both Kelowna and Coquitlam, but the base density allowed for existing single family use, including secondary suites and laneway houses, is also higher in Vancouver. Nevertheless, both remain lower than provincial guidelines for SSMUH. Moreover, demand to live in the area is higher in Vancouver, so it’s not clear how differences in density allowances translates.

Apart from differences in demand and existing vs updated density allowances, value capture efforts may be holding back some of the reform’s potential. The reform handicapped higher density multiplex options with amenity contributions to the City and/or other limitations (secured rental or “affordable ownership” units) put in place intentionally to keep land values low. Importantly, though the equity concerns go unrecognized by the City, this tips the scales to the benefit of the most expensive form of housing – single-family detached – and against prospective buyers willing to share land across multiple households. Nevertheless small-scale developers are proving more willing to try out the new forms on offer than anticipated by planning staff, perhaps in hopes that they can scale up multiplex in the future or otherwise better prepare themselves for future reforms.

A more successful multiplex reform would see the City actively encouraging multiplex instead of just conditionally permitting them under value capture conditions. Expediting permits for pre-approved forms of multiplex, as was done for Kelowna, would help! Of note, there have been moves in this direction. A OneCity proposal Streamlining the Provision of Duplex and Multiplex Housing in R1-1 Zoning exploring further reforms was put forward as a motion by Councillor Lucy Maloney in July and was unanimously approved by Council ahead of a forthcoming review of R1-1 zoning being prepared by staff. If, as we suggest, the devil is in the details for multiplex reform, there’s a still a chance to get him out!

More broadly, stepping out of the multiplex fixation, more successful housing reforms would see the City asking what form of housing would match demand to live in different parts of the city and generally work to enable those forms to get built. (von Bergmann and Lauster 2025) By contrast, the provincial SSMUH initiative just sets a new baseline for zoning, stepping up from single-family detached. The Transit-Oriented Area (TOA) initiative does the same by specifying new baselines near major transit investments. Cities can go beyond these minimums by allowing more people to share land for housing everywhere, and they can get an idea of what the outcomes will be by looking to current demand and proactively planning to let developers build to that demand. That doesn’t mean everywhere will look alike (indeed, its often planning constraints that reinforce cookie-cutter designs). Instead, providing greater flexibility for builders is likely to result in more diverse urban landscapes. Working through the implications for that kind of reform would return urban planning to a forward looking activity recognizing the value of city life for everyone rather than a backward looking activity reducing land values to protect the privileges of the select few who can still afford a full lot of their own.

As usual, the code for this post is available on GitHub for anyone to reproduce or adapt for their own purposes.

References

Dahmen, Joseph, Jens von Bergmann, and Misha Das. 2018. “Teardown Index: Impact of Property Values on Carbon Dioxide Emissions of Single Family Housing in Vancouver.”Energy and Buildings 170 (July): 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2018.03.012.

Lauster, Nathanael. 2016. “The Death and Life of the Single-Family House,” November. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvrdf3ms.

von Bergmann, Jens, Thomas Davidoff, Nathan Lauster, and Tsur Somerville. 2025. “Upzoning and Redevelopment: The Details Matter.”Journal of Housing Economics 69 (September): 102078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2025.102078. (open-access)

von Bergmann, Jens, Tom Davidoff, Albert Huang, Nathanael Lauster, and Tsur Somerville. 2023. “SSMUH and TOA Scenarios in British Columbia.” BC Ministry of Housing. https://news.gov.bc.ca/files/bc_SSMUH_TOA_scenarios_Final.pdf.

von Bergmann, Jens, and Nathan Lauster. 2021. “Lots of Opportunity: Estimating the Zoning Tax in Vancouver.”https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2021-07-25-lots-of-opportunity-estimating-the-zoning-tax-in-vancouver/.

———. 2025. “Demand Based Zoning.”https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2025-08-04-demand-based-zoning/.

Footnotes

- Vancouver amended it’s multiplex zoning to also allow multiplexes in RT-7, RT-9, and FSD zoning in June 2024.↩︎

- Some projects might have several building permits, which we collapsed in this count.↩︎

- Laneway houses can also be built on lots with existing single family homes as infill, we don’t show those here.↩︎