I’ve been away from blogging, in part due to various end-of-semester teaching and publishing tasks, and in part due to a minor obsession with US political developments. (And really, who isn’t at least somewhat obsessed by US political developments? But more on that in a moment.)

At any rate, I’ve been thinking a bit about taxes. Specifically property taxes. It’s striking to me that Vancouver has such really, really low property tax rates. This is most true in terms of actual property tax rates, with Vancouver’s at a low, low 0.35%, but it is still true even after accounting for Vancouver’s very high property values, resulting in low overall property tax payments. See relevant Canadian comparisons here and here. To look up (somewhat dated) US property tax data, see the Tax Foundation, or this report on average property taxes at the state level, where we learn that if Vancouver was a state, its tax rates would place it lower than every other state save for Hawaii. In case you’re wondering, the City provides a helpful description of how property taxes are calculated, and also a sense of where the money goes.And you can find comparative data for all BC municipalities here.

So Vancouver pays low taxes? So what? On an everyday basis, doesn’t that help make up for the extraordinarily high costs of real estate? Property taxes are a drop in the bucket compared to the local costs of buying a home, and if they were raised it would only make buying even more expensive and out of reach for locals. Unless…

- Low property taxes were fueling high prices

- Money raised from hikes in property taxes could be given back to local buyers and/or set aside to support more affordable housing options

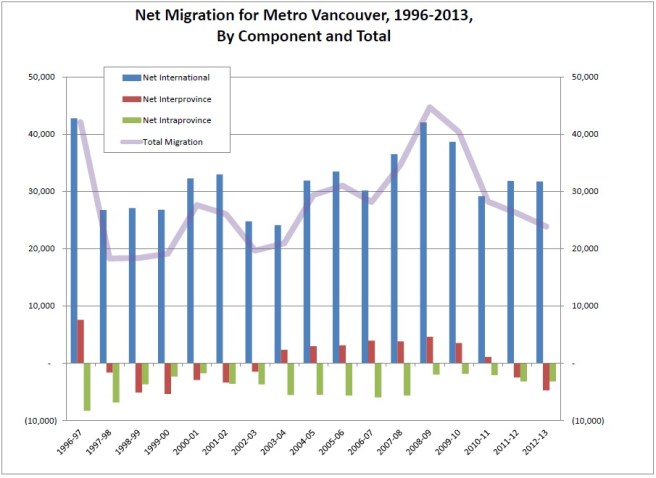

Low property taxes make it ridiculously easy to park money in Vancouver real estate as an investment, and there is a lot of money flowing into property across the metropolitan region. Real estate is an enormous driver of the local economy. But overall, incomes remain relatively low in Vancouver. So there’s a very good case to be made for re-balancing taxes away from income and toward property.

But inequality has also been on the rise in Vancouver, as elsewhere. Income taxes are progressive, falling more heavily on the wealthy, while property taxes are flat – every $1,000 in property is taxed at exactly the same rates. So a re-balancing away from income tax and toward property tax could be regressive. But why not tax property in a progressive fashion?

One suggestion is that property values over $1 million get taxed at a different rate than values below, with other progressive increases at higher cut-off points.

For example, the threshold for paying any surtax could be set at $1 million, with an initial rate of one per cent on the value above that, rising in steps to three per cent on values above $3 million.

To be clear, in this proposal owners would only be taxed upon the portions of their property value above the cut-offs. (i.e., someone owning a $1.1 million house would only pay the progressive tax on $100,000 of the value of their home). This sort of a progressive property tax could have many positive effects.

A progressive property tax could cool down the local property market, especially at the high end, where it’s been most overheated. At least some of the tax could be offset against income taxes, resulting in an entirely sensible re-balancing of tax burdens reflecting the low income levels relative to high property values in the region. Some of the tax could also be set aside to support more affordable housing locally, by, for instance, supporting more housing cooperatives.

I like it!

Elaborated variations on this kind of fiscal policy tweaking have been suggested by a team of economists (mostly led by Tom Davidoff) at both UBC and SFU, who offer a more flat-tax version attached to a housing affordability fund, and Rhys Kesselman and Josh Gordon (at SFU), who bring progressivity to the initiative and are quoted above. These are both worthy policy proposals (though I prefer to combine their best elements, bringing together the Housing Affordability Fund with the tax progressivity).

So what’s not to like?

Mostly the sales pitch.

As I mentioned at the outset, I’ve spent too much time watching the US election play out. I’ve also been following the rise of right-wing, xenophobic parties across Europe. I’m not so afraid of Trump (I really don’t think he’s going to do very well in the general), but his xenophobia and racism has proven far too popular for my taste. So popular that even the nice, elderly barber who cut my hair the other day here in Vancouver expressed approval of Trump (and he was an immigrant!).

It’s why I found this headline so heartbreaking:

Foreign buyers crushing Vancouver home dreams as governments do little: study

Yet this was the headline the Canadian Press (and/or CBC) chose to go with in announcing Josh Gordon’s recent policy paper. And this was the spin within the policy paper itself on why we need to re-balance toward a progressive property tax. It’s clear from a close read that most authors of various new property tax proposals direct their ire primarily at government inaction (looking mostly at you, Christy Clark). But who is it we’re most obviously directed to see “crushing” our “dreams”? Foreigners. Needless to say, one needn’t go far in the comments section of the article above to find praise for Trump and outrage directed at foreign buyers (“Ban them and confiscate their property!”).

There needs to be room here to support good, progressive policy without whipping up anger at foreigners and immigrants (who are too often conflated, in part due to the complexities of the transnational world we are living in). This is not to deny that money flowing into Vancouver, quite often (though not solely) from China, is driving housing costs, especially at the luxury end of the market (which in the City of Vancouver, let’s face it, includes all single-family houses). I don’t think that’s really in dispute. There’s a lot of money coming in to Vancouver real estate from China. But that money is here because the city and provincial and federal governments have all invited it in at various times in pursuit of common “growth machine” policies. There are good reasons to change some of these policies and I welcome that discussion as well as many of the policy proposals kicking around these days. There are not good reasons to demonize folks who’ve accepted so many of our governments’ invitations as “foreigners,” nor are there good reasons to “ban them,” or “confiscate their property.” That’s been tried before. It’s not the Canada I want to live in. But then, I’m an immigrant.

**Further update: still evolving, but many are

**Further update: still evolving, but many are